Human in the Loop

I love to take the temperature of the room when people start talking about AI, especially when it’s family members or folks who don’t have much to do with the tech industry.

Just last night I heard a relative refer seriously to the “end of the world” brought on by ChatGPT, and my conversations with speakers for this year’s Dent Conference reveal a broad array of fears and opinions on what modern AI means for the future.

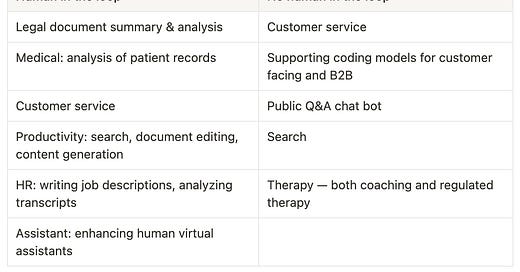

I also read Newcomer (well worth a sub for tech and VC coverage), and he recently got his hands on a pitch deck from Anthropic, the AI company behind ChatGPT-like bot Claude. In it, they divide the future opportunities for their AI technology by whether or not there will be a “human in the loop.”

That’s a great phrase, and an important one, because it cuts to the heart of what many people fear: that ChatGPT (or Claude, or Bing, or…) can do their job. Here’s how Anthropic breaks it down — note that customer service falls in both categories:

I have no reason to doubt this breakdown; presumably they know the capacity of their technology better than I do. And it shows a lot more potential for near-term enhancement of work than it does for replacement of work. If you spend a few hours playing with Claude or ChatGPT or Bing then I think you’ll find that you agree.

These bots make for great creative companions but lack the capacity for greatness themselves.

AI is therefore both completely revolutionary and disappointingly banal, like wi-fi on a transatlantic flight: it feels superhuman yet frustrates you with its limitations. But even enhanced productivity can still lead to fewer jobs. This is what happened to farming, as PBS nicely summarizes:

In the 1800s each farmer grew enough food each year to feed three to five people. By 1995, each farmer was feeding 128 people per year. In the 1800s, 90 percent of the population lived on farms; today it is around one percent. Over the same period, farm size has increased, and though the average farm in 1995 was just 469 acres, 20 percent of all farms were over 500 acres.

Like the seed drill, the rotary tiller, and the combine harvester, today’s AI tools are force multipliers across a broad swath of the economy. And like the children of farmers of 1850 I think that in the future many people will find themselves seeking new careers or jobs that don’t yet exist.

This is scariest for people in jobs like food service and shipping fulfillment where the combination of robotics and new AI technology is poised to turn the pace of automation up to 11. We do not have a good track record in this country of helping people who work in these types of jobs to feel like they are a part of an exciting technology change instead of the target of an exciting technology change.

Gilman Louie, who is my partner at Alsop Louie Partners and also a co-author on the National Security Commission report on AI, recently called for government and industry to work together to develop a “a comprehensive, safe, ethical, and responsible AI framework.” He’s more than right: we need to do this, and it should include measures that help people understand what the boundaries will be on how AI affects work. But it will take time to do.

Luckily I believe these kinds of job disruptions will be more gradual than they threaten to be, because as I play with these advanced tools I continue to find the limits of what they can do. Often in technology the last 20% of your feature set is disproportionately hard to do, and I would be surprised if that were different for ChatGPT and its ilk.

Right now, the social experimentation with AI is outpacing the technology, which makes things feel like they’re moving really fast.

Yesterday morning I read The Hustle’s story about the how AI-generated voices could crush the field of voice acting. In the afternoon I read that someone released an AI-created musical track that sounds like a collaboration between Drake & The Weeknd (it’s pretty good), and then I read that Grimes responded by suggesting that anyone should feel welcome to use an AI knock-off of her voice to create music, and she’d split the royalties 50/50 with the creators of any such hits. It’s hard to keep up.

But as the rough edges on the technology prove difficult to sand down, the pace will slow. People have a remarkable ability to become bored with yesterday’s miracles, and a knack for conjuring up ways to adapt to new technology that surprise us.